Roth 401(k) News: Is It Time to Rethink How You Save for Retirement?

The SECURE 2.0 Act, part of the federal spending bill passed in late 2022, ushered in new rules for workplace retirement accounts. For instance, starting in 2026, workplace plan participants with $145,000 or more in wages the prior year will no longer be allowed to make pre-tax catch-up contributions to a traditional 401(k) or similar plan. Instead, they can make after-tax contributions to a Roth account — if one is available. (In 2024, all workplace plan participants age 50 and older can contribute an extra $7,500 over the standard annual limit of $23,000. These amounts are indexed to inflation, as is the new wage threshold.)

Older workers in their peak earning years may initially lament the loss of a significant tax deduction. But in time, they may come to appreciate the nudge to contribute to a workplace Roth account, creating a source of tax-free income that they can tap into — or not — during their retirement years.

Roth 401(k) flexibility

Distributions from traditional retirement accounts are taxed as ordinary income, while qualified distributions from Roth accounts are tax-free if certain conditions are met. The conventional wisdom is that Roth contributions are advantageous when the taxpayer’s current tax rate is lower than the expected rate on taxable withdrawals that would be taken in retirement — a situation that is less common for highly paid employees near the end of their careers. Even so, contributing to a workplace Roth account could make sense for many of them. Here’s why.

A taxpayer’s retirement income (and tax bracket) might be difficult to predict. It may turn out to be higher than expected, especially if required minimum distributions (RMDs) from taxable retirement accounts (and/or inherited accounts) are added to the mix after years of potential growth. It’s also possible that tax rates will be higher in the future than they are today.

Roth distributions can be a powerful tax management tool. For example, a retiree could spend money from a Roth account in years that taxable distributions would otherwise push their income into a higher tax bracket, trigger taxes (or higher rates) on capital gains, net investment income, and Social Security income, or result in means-tested Medicare surcharges.

A Roth account could be a key part of an estate plan. The SECURE 2.0 Act eliminated the requirement to take lifetime RMDs from Roth 401(k)s and similar employer plans, bringing them in line with Roth IRAs (effective in 2024). Unlike a traditional account, investments in a workplace Roth account could be left untouched (or rolled to a Roth IRA) to accumulate for as long as the owner is alive, and the tax-free money can be passed on to heirs. (Beneficiaries must take RMDs.)

Employee Access to Roth 401(k) Plans on the Rise

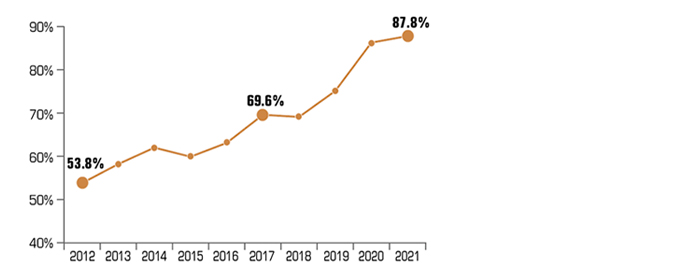

The percentage of employers offering a Roth 401(k) plan grew substantially from 2012 to 2021, a trend that’s likely to continue.

Source: Plan Sponsor Council of America, 2022

Even small Roth contributions start the critical five-year clock. A Roth distribution is considered qualified, or tax- and penalty-free, if the account is held for five years and the account owner reaches age 59½, dies, or becomes disabled. (Other exceptions may apply.)

More changes will sweeten savings opportunities. Starting in 2025, workers age 60 to 63 will be able to make additional “special” catch-up contributions (of up to 150% of the regular 2024 catch-up contribution limit or $10,000, whichever is greater) to 401(k) and similar workplace plans. And employers can offer the option for employees to receive matching contributions to the plans on a pre-tax or after-tax basis. Employees will owe taxes on Roth matching contributions in the year they were made, but such contributions are required to be 100% vested immediately.

These changes were intended to draw attention to employer-sponsored Roth accounts and help expand their role in the U.S. retirement system. Thousands of large employers don’t yet offer a Roth option. However, the 2026 deadline should give companies enough time to amend their retirement plans accordingly.